„Connection is the point“ - Photographer Kim Weston in conversation with Thomas Berlin

Conducted for Fine Art Photo Magazine, Issue 39

Kim Weston

Kim carries the photographic legacy of his family—especially that of his grandfather Edward Weston, an icon of American photography—while forging his own distinct artistic vision. In this profound conversation with Thomas Berlin, Kim discusses intuition, vulnerability, and the essence of art—a journey through the darkroom, the studio, and the philosophy of life.

Thomas Berlin: Kim, this interview is about your own photography. At the same time, you are part of a dynasty of photographers that goes back to Edward Weston, whom we will talk about later. When you think about your photographic journey, was there a moment when you realized that photography was more than just a family tradition for you?

Kim Weston: I started photography when I was six years old. My earliest memories are of sitting on a stool in my father's darkroom because I was too small to reach the sink. I was always excited about it. I loved the darkroom. I was a very shy kid. It was just me and my dad in there, and it was dark.

Thomas Berlin: What were the first steps in taking photographs yourself?

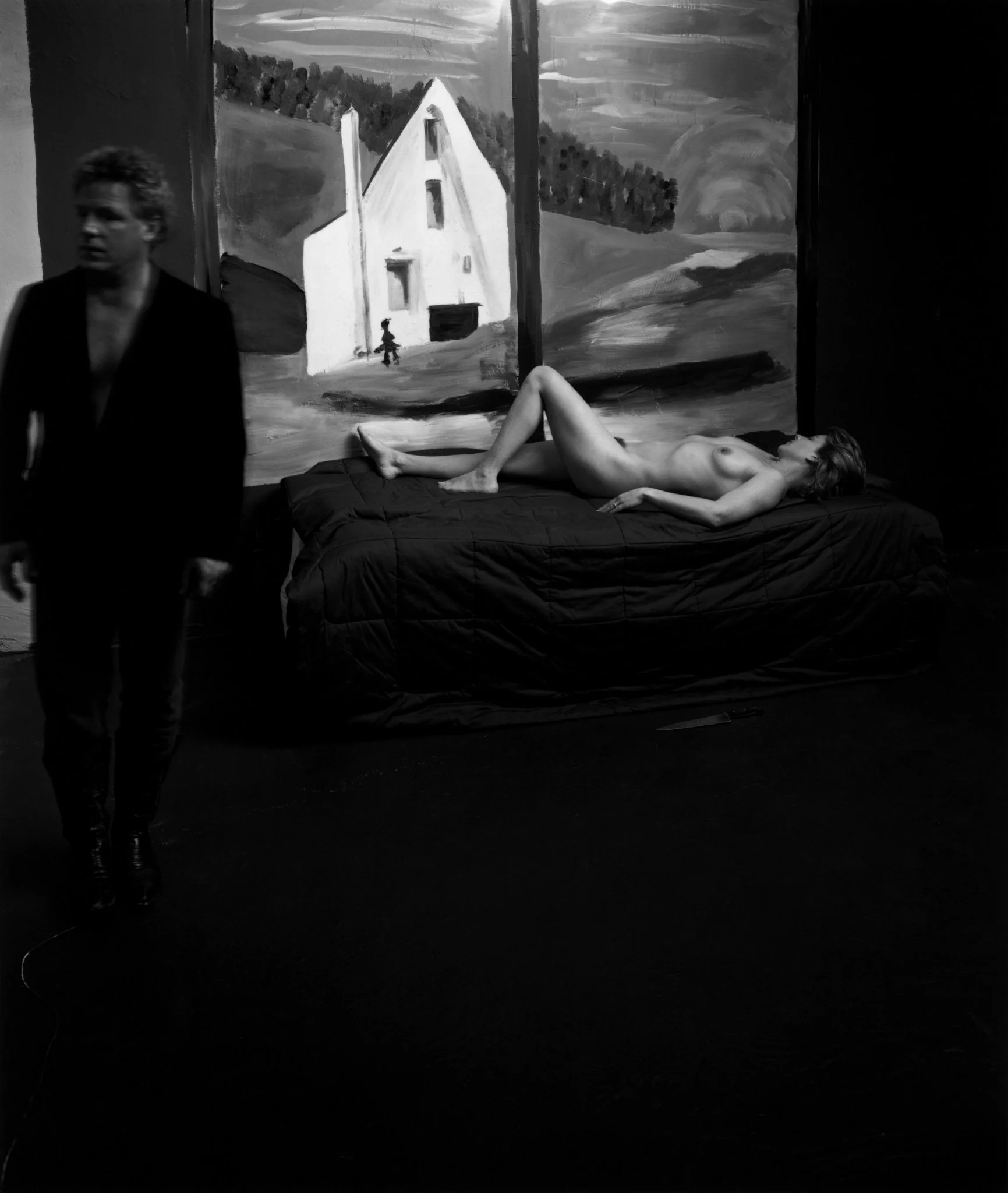

Kim Weston: In the beginning, I photographed in the Weston tradition with my dad Cole Weston and my uncle Brett Weston—rocks, trees, and landscapes. As I got older, I didn't want to simply follow in my family's footsteps. I needed to do something that pleased myself. I found I wanted more control over filling the rectangular frame. With landscape photography, your control is limited to composition, lighting, and timing. So I gravitated toward the studio, where I could build and paint sets and bring in models.

Thomas Berlin: What was more appealing about photographing models instead of landscapes?

Kim Weston: I wanted to work with models because I love human interaction. With landscape photography, it's just you and whatever beautiful scene you encounter. But working with another person is a much more complex challenge. So I ended up in the studio for over thirty years, where I had complete control over every element in my photographs. I built and painted the sets myself—it was a hands-on process entirely different from landscape work. Through these constructed environments, I could work through whatever was happening in my life at the time, whether emotional struggles or other personal challenges.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: You painted the sets for the studio yourself?

Kim Weston: Yes, I was always influenced by painters. Most of my inspiration came from them. I'd get books and flip through them, studying painters like Degas and Balthus. I have a whole list of painters who inspire me. But it wasn't a conscious decision to differentiate myself from my grandfather. My dad, on the other hand, deliberately moved into color photography so he wouldn't be compared to his father. With such a famous father, he wanted to forge his own path, so he made that conscious choice. For me, it happened more naturally—the type of photography I do is deeply personal. It's all about what I want within that rectangular frame, which makes it far more complex. And I thrive on that complexity.

Thomas Berlin: Tell me about your first steps with photographing figures in front of your camera.

Kim Weston: What's important is the interaction with another human being. You're making art together as a team, which is probably the best part. In the beginning, I photographed my girlfriend and her daughter—they weren't professional models. Then I met Gina, who modeled for me for about twelve years. One day she told me she wasn't going to model anymore, and I was taken aback. I had never used professional models before. There was always this real connection between my photography and the people in my life.

Switching to professional models meant changing my entire approach. That's why I ended up working with the same models for years. We built real relationships. They weren't just figures to photograph; we were collaborators working through ideas together, and that human connection was essential.

I still photograph landscapes for fun. One of my best friends, Roman Loranc, is a landscape photographer, and I go out with him into the wilderness. I still love it. But working with models and building sets allows me to add more layers to the story. I'm a storyteller at heart, and this approach lets that narrative quality naturally unfold.

Thomas Berlin: The term "storytelling" is interesting in this context. In your grandfather’s work, I see photography as a reduction to form and light—almost sculptural. In your work I sense more narrative and atmosphere. How would you describe the difference between your grandfather`s, your father`s, and your own approaches?

Kim Weston: Edward, my grandfather, was a straight photographer. If you stood beside him when he made a picture, the final print looked exactly like what you saw. That was the essence of Group f/64: no manipulation, no altering the image through development or printing.

My uncle loved abstraction, even though he`s best known for large landscapes. He was fascinated by how exposure, printing, and paper could transform reality. Edward wasn`t like that—he wanted pure reality.

Interestingly, some of Edward*s best-known works—his nudes and peppers— were collaborative. They involved a relationship with his model, often his wife or partner, or with the still-life objects he arranged in the studio. The famous Pepper No. 30, for example, was photographed in a metal funnel during the time he experimented with thirty-seven different peppers. That act of arranging and shaping within the studio connects him, in a way, to my own practice.

A photograph by Edward Weston (1886–1958), Kim's grandfather. © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

“Pepper N. 30” - A photograph by Edward Weston (1886–1958), Kim's grandfather. © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: Your grandfather founded the f/64 group together with Ansel Adams, who also strove for an accurate representation of reality. Before them, the pictorialists tried to make photographs look like paintings. This brings me to one aspect of your work: you sometimes added oil paints or pastel chalks to your black-and-white prints, completely changing their character. Is this inspired by pictorialism or more of a hybrid approach?

Kim Weston: My influence comes from painters. I`ve always been fascinated by how paint can change the entire mood and feeling of an image. I could never start with a blank canvas, but painting on my own photographs lets me build another layer of story on top of an existing subject.

With painting, the same image can be reinterpreted endlessly and it`s no longer bound by the photograph itself but by how I apply the paint. Photography ends with the image; painting keeps going. I like that. I`d been photographing for fifty years, I know my craft, but I wanted something new—something I could fail at. That sense of uncertainty felt essential, almost like returning to the excitement of being a child making the first photograph. Painting gave me that risk.

Thomas Berlin: Since you mentioned failure, I think that ultimately you are not risking anything when you try something new in art.

Kim Weston: Yes, exactly. You're absolutely right, but it's important to keep challenging yourself and trying new things. When you go to a museum or look at other people's work, you tend to be a bit reserved and view the photo with a kind of reverence that it commands. Painting is something I can do at any time of the day or night. So, I'm open to it instead of being a kind of slave to light. And that, as is the case with photography, gives me the opportunity to paint at night or whenever I feel the urge to be creative. Photography is very strict in that regard, because it's all about light and atmosphere and whatever. But painting gives me the freedom to be creative at any time of day.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: It starts with a blank page — your original photograph — and the rest is up to you?

Kim Weston: Yes, and another interesting question is: When do you stop? When do you stop applying paint? I don't know if you've ever worked with oil paint, but it's a very messy business, and if you overdo it, it turns into mud.

Thomas Berlin: Yes, I did. You have to be very patient with oil paint because it dries so slowly. That's why I switched to acrylics.

Kim Weston: I wanted that—the slow-drying quality of oil paint. But I didn't want the process to become precious or overworked, like some kind of paint-by- numbers. So right from the beginning, I set myself a time limit of fifteen minutes. I wanted to throw myself into it and attack it, you know? And then there is the real challenge—when do you stop putting paint on?

“The finished image is static, but what it captures is everything that led up to that moment.”

Thomas Berlin: If you stop, will you continue after a few days?

Kim Weston: No, I never go back to it. It was just an exercise that I needed. Once I finished, I didn't question it. I know a lot of painters rework things, especially with oil, because you can while it's still wet. But I didn't want that—I wanted it to be definitive. When it's done, it's done.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: We talked about natural forms and the human body. You`ve said that collaboration with the model is central to your work. How do you view the human figure—more as a form or as an expression of emotion?

Kim Weston: It depends on the project and what*s going on in my life. Early on, when I worked mostly with non-professional models, the model often stood in for me.

I remember a trip to New York many years ago. I grew up in the country, went to a one-room schoolhouse—so New York completely overwhelmed me. The crowds, the noise, the indifference of people—it was shocking. I had planned to photograph outdoors like my uncle Brett did, but I ended up staying in a friend`s tudio instead.

When I came home, I built my own version of New York in my studio—tiny buildings, streets, crowds—and then placed a model inside. She became a stand- in for me, representing my own vulnerability and fear of the city. That kind of projection often appears in my work.

Later, when I began working with professional models, the process became a true collaboration. We would look through books together—painters like Balthus, whose work fascinates me because of his compositions and subtle tension—and create something inspired by those references. The model adds her creativity; she suggests poses, interpretations. A great model is an artist in her own right, using her body as a brush. That collaboration is what excites me most.

Thomas Berlin: So the model becomes like an actor, and you direct together?

Kim Weston: Exactly. In the beginning, when I worked with friends, I was the director. But with professional models, it became a dialogue. Sometimes they would direct me. The photograph is just the final piece of a much larger process—building and painting sets, choreographing movements, sharing ideas.

When I`m working like that, the camera records not only the model but also the energy between us. The finished image is static, but what it captures is everything that led up to that moment.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: In staged photography, how important is it for you to convey not only form and structure but also emotion?

Kim Weston: It`s absolutely essential. When I go to exhibitions, I often see people glance at a landscape for five seconds and then move on. Those images may be beautiful, but they don`t challenge the viewer. I want my pictures to make people feel something—joy, unease, tenderness, discomfort—anything genuine. I admire painters like Balthus for that reason. His work leaves so much open to interpretation; it invites questions, even tension. That` what I want—to create a dialogue between the photograph and the person looking at it. It does`t matter if the viewer understands what I intended. What matters is that they feel something.

It`s the same reason people can stare at a Jackson Pollock painting for an hour—it forces them inward. I want my images to stop people, make them think about themselves, not just admire the surface.

Thomas Berlin: Is it important for an image to raise questions?

Kim Weston: Yes. Even my grandfather’s photographs do that. People look at them and see shapes that are sensual, human, almost erotic. Then they realize it*s just a vegetable. That moment of uncertainty is the hook—it makes you stop and think.

Thomas Berlin: Do you aim to tell a story with your photographs, or does the story unfold in the viewer`s mind?

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Kim Weston: I’m definitely telling my own story. But it`s personal—created for me, not for an audience. My friend Roman often says, „They`re going to love this,“ after making a photograph. I`ve never said that. I`ve never cared whether someone else would love my work. For me, photography is self-centered in the best way. I build the sets and make the images because I have to.

Thomas Berlin: Does that mean the audience comes last?

Kim Weston: Absolutely. If someone likes it, great. If you make a connection, great. But basically, the connection I'm making is with myself and the artwork I've created.

Thomas Berlin: Maybe viewers can still create their own stories, even if they differ from yours.

Kim Weston: That`s exactly what I want. I don`t care if people don`t understand my intentions. I hope they connect with the image on their own terms and learn something about themselves through it. That`s far more rewarding than them simply „getting“ what I meant.

Thomas Berlin: You`re known for your nude photography. Why do you focus on that subject rather than, say, flowers or portraits?

Kim Weston: For me, its about collaboration. The human figure allows for complexity—emotion, story, interaction. Some of my images are purely about form, but others are deeply personal. I never wanted to confine myself to one theme.

Years ago, a gallery sold one of my photographs—Gina with calla lilies, inspired by Diego Rivera. The dealer came back and said, „You should make more of these.“ I said „No.“ That`s the trap of the art market. Galleries want consistency—they want a brand. My friend Roman, a landscape photographer, can`t even show nudes because his gallery insists on landscapes.

So I pulled my work from galleries altogether. I didn`t want to become a product. Selling isn`t worth the loss of freedom.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: Do you find that nude photographs are harder to sell in general?

Kim Weston: Definitely. I`ve had people tell me, „I love this, but I can`t hang it in my house—my spouse wouldn`t approve.“ It`s absurd when you think about it. The nude has been central to art since the beginning—painted, sculpted, celebrated—and yet it still makes people nervous. Books work better; you can hide them on a shelf. But I won`t change my work to please the market.

“Art is a way to learn about yourself.”

In recent years, I`ve been photographing more clothed figures. Clothing adds another narrative element—it says something about identity, age, and personality. One of my current muses is the daughter of a close friend. I began photographing her when she was twelve, always clothed, and now she`s fourteen. I hope to keep working with her as she grows. Her clothes, gestures, and presence each tell part of a larger story.

So it`s not about nudity itself. Nudity can be powerful because it reveals vulnerability, but it`s not a requirement. For me, the nude is about honesty— about stripping away pretense. That same vulnerability exists in clothed portraits too, if you`re willing to look for it.

I've even done a whole series of nude self-portraits—just for myself. I gave them to my wife Gina one Valentine`s Day. I wanted to experience what it feels like to be on the other side of the lens, to be seen, to be exposed. It completely changed the way I work with models.

Art, to me, is a form of learning—learning about yourself. If you don`t take risks, if you don`t allow for failure or discomfort, you never really understand what you`re doing or why. That`s why I keep pushing into new territory.

When my son was young, he would often be in the studio with us while I photographed Gina. One day, after we finished, he looked at me and said, „Dad, is it my turn?“ It was such a simple but profound moment—he wanted to be part of that creative process. That openness, that sense of play and curiosity, is what I try to hold on to.

“Connection is the point.”

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: How do you create an atmosphere that fosters that kind of openness—music, tea, conversation?

Kim Weston: Every model is different, every session unique. I do whatever makes them feel comfortable. During workshops, I sometimes use music because many photographers hide behind their cameras. They click the shutter without ever talking to the model, as if communication weren`t part of the process. I tell them: that`s another human being in front of you. You need to connect. Talk. Collaborate. Otherwise, you`re just taking pictures, not making them.

When I work on my own projects, I rarely use music because we`re always in conversation. It`s not about background noise—it`s about presence. The real art happens in that space between two people. Connection is the point.

Thomas Berlin: On your website, you advise photographers to bring a tripod to your workshops. In a world of digital stabilization, why the tripod?

Kim Weston: Because it forces people to slow down. A tripod demands intent. It turns every exposure into a decision. When I teach workshops, I make everyone start with a tripod. Later they can move freely, but that mindset—thinking before pressing the shutter—has to stay. Digital photography encourages people to shoot in bursts: click, click, click. You cant truly see like that.

I learned on large-format cameras—8x10 especially. That camera teaches discipline. Every exposure costs time, money, and effort. You study the scene, adjust the light, and commit. After my father passed away, I inherited his Mamiya RB67. Moving from 8x10 to 6x7 felt like putting wings on the camera—I could finally move around the model with freedom. I worried about image quality at first, but the new films and papers are incredible. I can easily print 20x24 inches from a 6x7 negative and still retain that depth and tonal range.

“Truth, clarity, and honesty.”

Thomas Berlin: Another benefit: with the camera locked off, you can step out from behind it and look directly at the model.

Kim Weston: Exactly. With large-format, once you insert the film holder, you can`t see anything through the lens. That forces you to step forward, to engage. You`re not hiding behind the machine anymore—you`re present with the person. That, again, is what matters. Too many photographers use the camera as a shield instead of a bridge.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: What makes a good photographer—or a good photograph?

Kim Weston: Someone who works for themselves first. You have to create because you need to, not because you expect praise or sales. For me, truth, clarity, and honesty are everything—both in photography and in life. I`m a photographer 24 hours a day, even when I`m cooking or gardening. Cooking, in fact, is a close cousin to photography: chemistry, timing, presentation—It`s all there.

Thomas Berlin: I rarely ask about kitchen equipment, but how important is photography equipment?

Kim Weston: I like to keep my tools simple. My grandfather`s darkroom consisted of one light bulb, a contact printing frame, a few trays, and a three- minute egg timer. Primitive—and yet he made masterpieces. That simplicity forced him to focus on essentials.

Modern equipment is wonderful, but it can become a distraction. Photographers sometimes think a new camera will make them better. It won`t. A camera is just a light-tight box. The simpler it is, the fewer excuses you have.

Thomas Berlin: You still work with film, a darkroom and hand-printed photographs. What does analogue craftsmanship mean to you in the digital age?

Kim Weston: My process hasn`t really changed since I was six. The darkroom is simply a means to an end. I don`t worship the process—It`s a tool, like the camera.

If I spend too many hours on one print, it usually means I`m struggling with the materials, not the image. When I make a new negative, I can produce a finished print in about an hour. Then I`ll pin it on the wall and live with it for a few days. Later, depending on how I feel, I might print it differently.

That`s what I love about analog—each print carries its own emotion, its own mood. Digital excels at repeatability. Every print can look identical, which is fine for some, but not for me. I often joke that I wish my printer had a button labeled „I`m unhappy today“ so it could match my mood swings.

“The value lies in the image, not in the process”

Thomas Berlin: Many analogue photographers have a hybrid workflow, i.e. they take analogue photographs and scan the images. From that moment on, they work with the digital version and also print digitally.

Kim Weston: It makes sense in some cases. I use digital negatives myself for platinum printing, which is a contact process—the print is the same size as the negative. Creating digital negatives gives flexibility: students can shoot digitally and still make true platinum prints. It bridges old and new worlds beautifully.

I have a friend, Huntington Witherill, who worked analog his whole life but eventually had to stop because of chemical sensitivities. When he switched to digital, he didn`t just replicate his analog style. He embraced what digital could do—using Photoshop creatively, altering reality, expanding his vision.

What puzzles me is that he sells his digital prints for less than his analog ones. That doesn`t make sense. The value lies in the image, not in the process. If we priced art based on equipment or effort, we`d have to charge more for photographs taken with expensive cameras like Leicas and less for those made on cheaper ones. That`s absurd.

I`ve recently made digital reproductions of my painted photographs so that I can print multiple editions. They`re still my work—every bit as personal. So yes, I charge the same for them. The process doesn`t define the worth—the vision does.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: When is a photograph a work of art—or is that distinction even relevant?

Kim Weston: I don't think that matters. The entire art market is a strange construct. People buy art for reasons that often have little to do with the work itself. My grandfather sold prints for thirty-five dollars that are now worth over a million. That's absurd—but that's how the system works. I accept it, but I also laugh about it. Art should be about growth, not speculation.

Thomas Berlin: I recently wrote a review of your new book for Fine Art Photo Magazine. But please feel free to tell us something about it yourself.

Kim Weston: I always wanted to do a book. I used to look at my grandfather's and my friend Roman's books, but I never felt ready—my work was an ongoing part of my life. Stopping at fifty didn't make sense; there was still so much evolving. I figured no one would take me seriously until I was seventy anyway.

For ten years, I mounted the negative on the back of each print to remind myself that the image wasn't sacred—it wasn't about one great image, but about growth as an artist. What mattered was the process. Many photographers get stuck in the past; I wanted to move forward. When I met Gina, she told me to stop doing that, and she was right. But I had to prove to myself that I could let go.

So when I finally made the book, I wanted it to encompass a full life`s journey. It took six years, with lots of help from friends — especially Gina, who`s meticulous with details. If I`d done a book earlier, it wouldn`t have included the painted work that came later.

The book is deeply personal — connected to my family and my models, who even wrote their own sections. Some people said I revealed too much, but I`ve never felt the need to hide. I just wanted the book to reflect everything — from my earliest work to now.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED

Thomas Berlin: Your Place Wildcat Hill near Carmel in California has a history—it was Edward Weston`s home and studio, and today it`s yours. What role does this place play in your inspiration?

Kim Weston: It`s huge. The only time I met my grandfather was here, at this very house where I now live. I was five years old. He was shuffling around the kitchen—very old, already affected by Parkinsons. To me, he was just „GP“ Grandpa. I had no idea he was a famous photographer.

And now, all these years later, I`m sitting at the same table where I first met him. It`s the same table my uncle Brett built. When Gina and I moved in, there were only two original pieces of furniture left—this table and Edward`s chair. That sense of continuity is profound.

People contact us and ask if they can visit the house. I always say yes. It`s like living in a living museum. The walls hold memories—the same light, the same views. I`ve collected everything I could find from my grandfather`s time: his desk, cameras, old prints, notes. It`s not nostalgia—It`s connection.

Thomas Berlin: From my conversation with your wife, I understand that Weston Photography is very much a family business—workshops, printing, the website. How do you divide the roles between you?

Kim Weston: Gina is the business mind. I`m not. I can barely get my computer to work. She runs the workshops, the website, the communications—everything.

When we met, she was a massage therapist, and I was a carpenter. Id been building houses for thirty years. One day I told her, „I don`t want to do this anymore.“ I knew I couldn`t make a living just selling prints, even with the Weston name—especially not with nude photography. So I asked her to take over the business side, and I`d focus on the art and teaching.

At first, I was shy. Speaking to groups terrified me. But I decided I had to grow beyond that. Art pushes you to evolve as a person, and the workshops helped me do that. Gina learned photography from scratch—she even took classes so she could answer questions from students who called. Now she handles everything behind the scenes. We`re opposites, but together we make one functioning human being. Alone, we`d both be lost.

Thomas Berlin: Kim, thank you for your openness and depth. Would you like to add something in conclusion?

Kim Weston: Just that I love what I do. I feel incredibly fortunate to live this life, surrounded by art and family. Our son is now following in my footsteps—he`s a wonderful photographer in his own right. Seeing that continuation means everything to me.

Your thoughts and reflections on this interview are very welcome here.

The interview was conducted in October 2025 by Thomas Berlin for Fine Art Photo Magazine, a high-quality print publication. Issue 39 will feature a portfolio presentation by Kim Weston.

© Kim Weston ALL_RIGHTS_RESERVED