„Curiosity—not judgment“ - Photographer Platon in conversation with Thomas Berlin

Platon

From presidents and dictators to unknown defenders of human rights — photographer Platon has faced them all through his lens. His portraits of power are iconic. Yet beyond the world of presidents, pop stars, and CEOs lies another body of work — one that centers on dignity, courage, and the universal language of humanity.

Thomas Berlin: Hi, Platon. I was just looking through your book THE DEFENDERS..

Platon: Ah yes, the big one. That book nearly ruined me. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but probably the one I’m most proud of.

Thomas Berlin: It also changed how I see your work.

Platon: Oh yeah?

Thomas Berlin: I used to think of you primarily as a photographer of powerful people—presidents, CEOs, icons of pop culture. But then I discovered other projects, portraits of people outside those circles. That changed my perception completely. Maybe it’s a shift in your work—or perhaps it ties together under one word you often use: empathy.

Platon: It’s interesting you say that. With creative people—filmmakers, writers, photographers—what you see as a new end product is often something the creator has been developing for years. The work in that book goes back two decades. It took me twenty years to travel the world, to build those relationships, and even longer to establish the infrastructure that made it all possible.

Thomas Berlin: By infrastructure, do you mean The People’s Portfolio?

Platon: Exactly. Forget creativity for a second—it took years to set up a proper foundation with a board of directors, so we could raise our own funding and go on missions the mainstream media simply weren’t interested in. I wanted to invest proper resources to amplify extraordinary people around the world who were being ignored.

Thomas Berlin: How did your media background influence that realization?

Platon: I came from the media—I’m a media baby. I’ve had the privilege of working with some of the greatest institutions and legendary editors and photo directors. But over time, I realized I was seeing the world through a narrow lens, and there were vital stories that weren’t being told.

Thomas Berlin: Because of how media operates?

Platon: Exactly. Media is also a business. They care deeply, but they also have to chase numbers and metrics. The good ones want to tell meaningful stories—but at what cost? Who’s going to dedicate twenty pages to celebrate unknown people bringing so-called “bad news” to the world? It doesn’t boost circulation. It’s not a criticism, more an acknowledgment: the structure of media felt less curious than I needed it to be. I felt confined.

Thomas Berlin: So you decided to take another route?

Platon: Yes. There was no platform that said, “Here’s $300,000—go cover the Egyptian revolution and bring a film crew.” And just to be clear, that money wouldn’t be for me—it’s production costs. I don’t work alone with a small camera. I have a big team; we also shoot films. We’ve built studios in places like Tahrir Square, or driven across the Mexican border amid the immigration chaos. It’s a serious operation.

Thomas Berlin: And that means you need partners who truly understand those environments.

Platon: Absolutely. You have to work with people who know the subject matter—Human Rights Watch, the United Nations, or small grassroots organizations deeply rooted in their communities. Building those relationships takes years. And then there’s post-production—research, editing, finishing. I had to build that infrastructure from scratch because it didn’t exist for this kind of storytelling.

Thomas Berlin: War correspondents have systems like that—but you were creating a new one.

Platon: Exactly. War reporters usually work lean—with a fixer and a writer. But when you’re traveling with fifteen people, building studios, hauling gear, filming, documenting—that’s a massive undertaking.

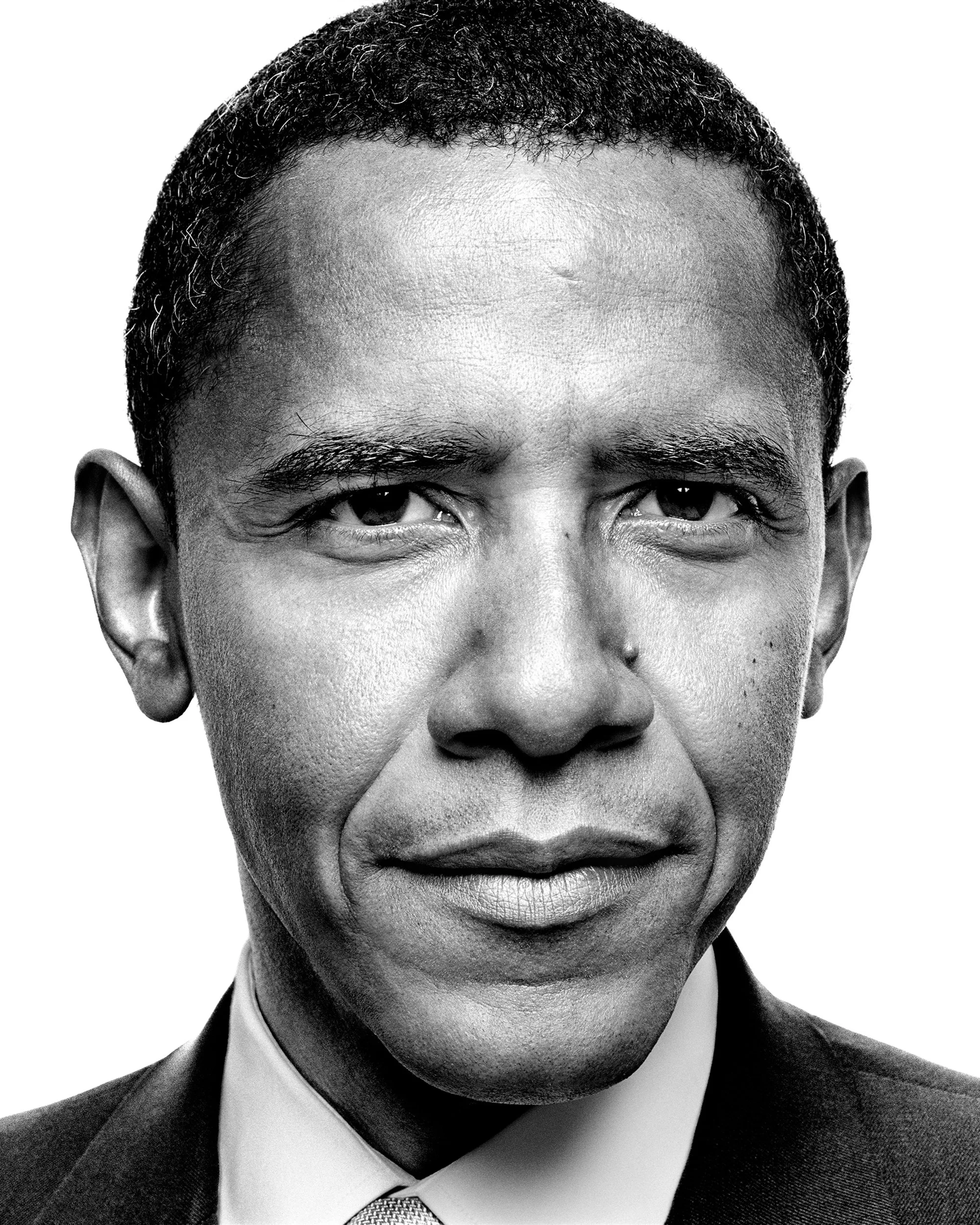

Barack Obama

Thomas Berlin: A huge production the media can rarely support.

Platon: They simply can’t afford it. Whether it’s undervalued or just underfunded, the point is—it doesn’t happen. So I decided to hack the system.

Thomas Berlin: How?

Platon: I was trained by George Lois—probably the greatest creative director in history. He made those iconic Esquire covers in the 1960s, using popular culture to provoke society about race, women’s rights, and human rights. He taught me to be a cultural provocateur—to think like an activist and use media to provoke debate. And of course, when you do that, you get backlash. But that’s the point. Holding up a mirror isn’t comfortable. If you’re not in good shape, you don’t like what you see—and the same goes for society.

Thomas Berlin: You also had extraordinary editorial opportunities. How did those shape you?

Platon: I did well in that system—lots of TIME covers, countless magazine spreads. I was given Avedon’s contract at The New Yorker, which is probably the most prestigious magazine you can work with. After Avedon died, they wanted to revive that visual voice, and I got the position. I learned so much about long-form photo essays. Every shoot changed my outlook—I was exposed to new ideas, new people, and their struggles.

Thomas Berlin: Do you remember one that left a particular mark on you?

Platon: One of my first big essays was a tribute to the American civil-rights heroes of the 1950s and ’60s. That assignment lit something in me—it showed how photography can honor courage and provoke debate. But The New Yorker is primarily a written-word magazine. One photo page there is worth twenty elsewhere. So when I started getting ten or fifteen-page spreads, that meant ten writers weren’t being published. For them, that was huge.

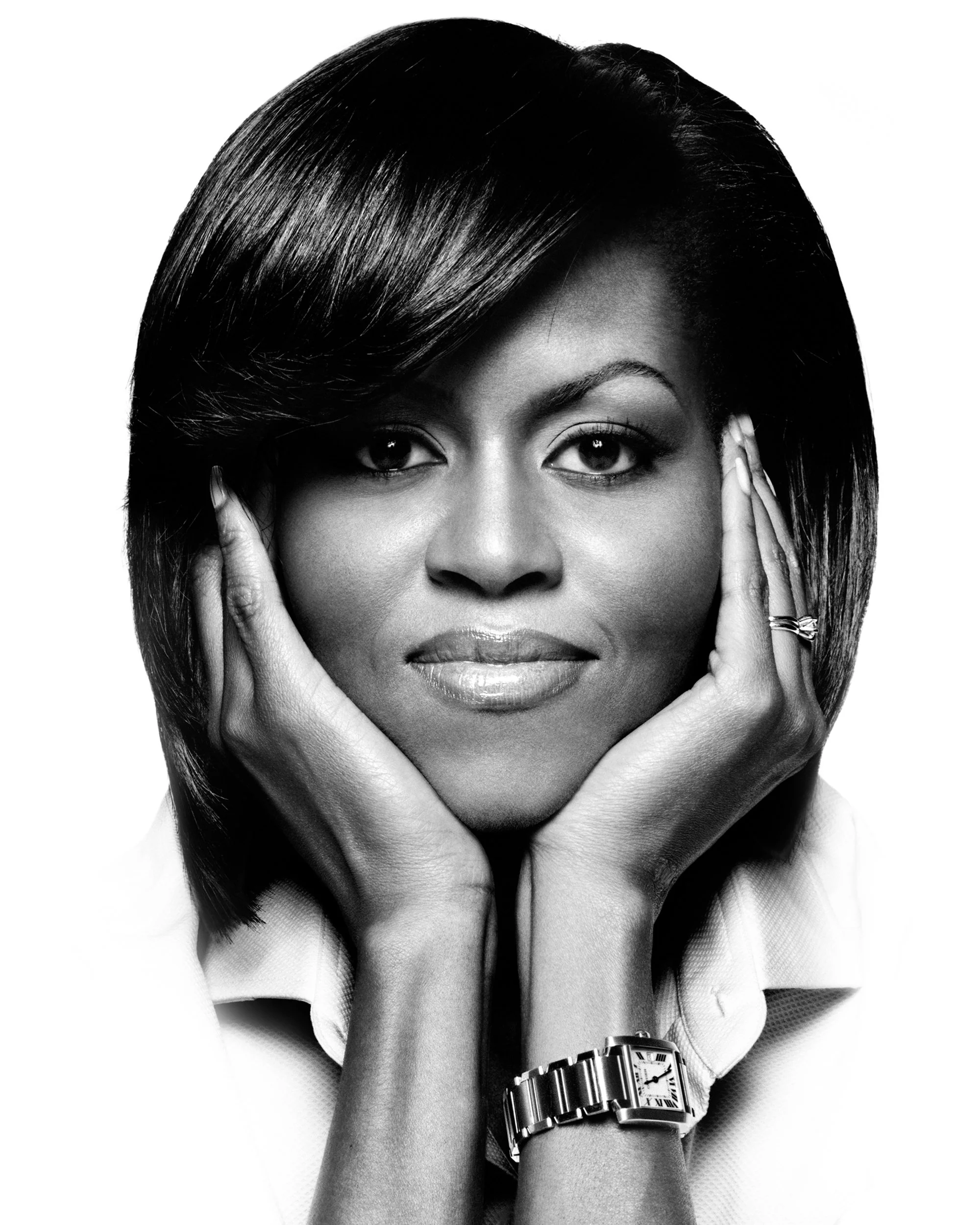

Michelle Obama

Thomas Berlin: That was the time you started World Leaders — your iconic portrait series of powerful people, which later appeared in your book POWER PLATON, right?

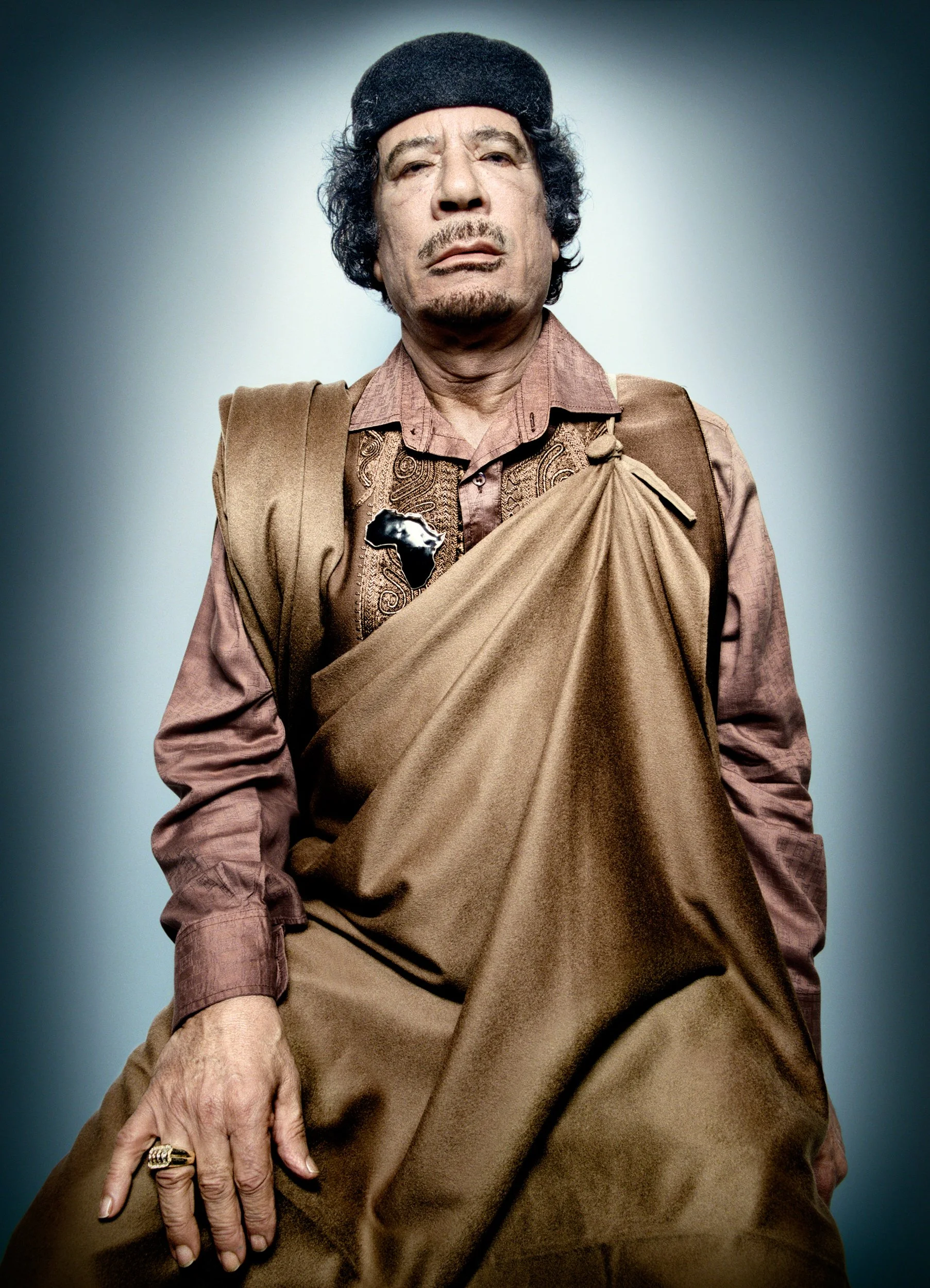

Platon: Yes. The book you’re looking at started as a New Yorker essay. Nobody expected me to photograph over a hundred world leaders—none of them had agreed in advance to sit. But I hustled, persuaded, negotiated. In the end, I came back with about 150 portraits. When David Remnick, the editor-in-chief, saw the layout—Gaddafi, Netanyahu—he couldn’t believe it. He dedicated an entire issue to the series. That’s about as good as it gets in our world.

Thomas Berlin: That must have been a career boost.

Platon: It was. But you only get that kind of moment once or twice. After that, I wanted to turn my focus away from those who hold power to those who have been robbed of it. And that’s where things get complicated—because world leaders have currency, while unknown human-rights defenders don’t. Space inevitably shrinks when you focus on the powerless.

Thomas Berlin: Is that when you decided to self-fund your work?

Platon: Exactly. I started fundraising so I wouldn’t be a financial burden on magazines or grassroots partners. I wanted to be self-sufficient—to do the work independently, then go back to my media friends and say, “I’ve got a big, timely story filled with extraordinary unknown people. I’ll give it to you for free—but run it big.” I thought that was a fair deal.

Thomas Berlin: And yet, even that wasn’t easy.

Platon: No, it wasn’t. It took me a year to convince TIME to publish my immigration story. Obama was still in power, the border crisis was quietly growing—families torn apart—and it was inconvenient to discuss. I warned that if it wasn’t addressed, someone would eventually exploit it for political gain. I saw that five or six years before Trump even announced his run.

Thomas Berlin: And when TIME finally published it?

Platon: They ran it online only. But at least it started a conversation—a dialogue about the human side of immigration, not just the numbers. I’m not there to provide solutions; my job is to ask questions and to humanize crises.

Thomas Berlin: Had you already thought about a book back then?

Platon: The book THE DEFENDERS became the culmination of twenty years of work. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done because I wrote 80,000 words—and I’m dyslexic. But I didn’t want an academic book by an “expert.” I wanted front-line stories—moments of intimacy from the set, from the van between locations, from an old woman’s house crammed with our gear. I wanted readers to feel the vulnerability, strength, and courage I witnessed.

Thomas Berlin: That seems like a very human approach.

Platon: Exactly. If someone like you reads it and then talks about it with friends or family, I’ve done my job. That’s how I fulfill the promise I made to the people in the book: to tell their stories.

Thomas Berlin: The written part feels essential. We often say a picture tells more than a thousand words, but here, context really matters.

Platon: I felt the same. With famous people, you can rely on recognition—show Barack Obama or Donald Trump, and everyone brings their own context. But if you show a young girl who survived sexual violence in Congo—her struggle to heal, to stand strong, to tell her story with compassion—you need context. These aren’t people the world already knows. I surrounded myself with incredible collaborators to handle their stories with the care they deserved. I’m glad the book is out there. Once readers connect with it, it’s no longer mine—it’s theirs.

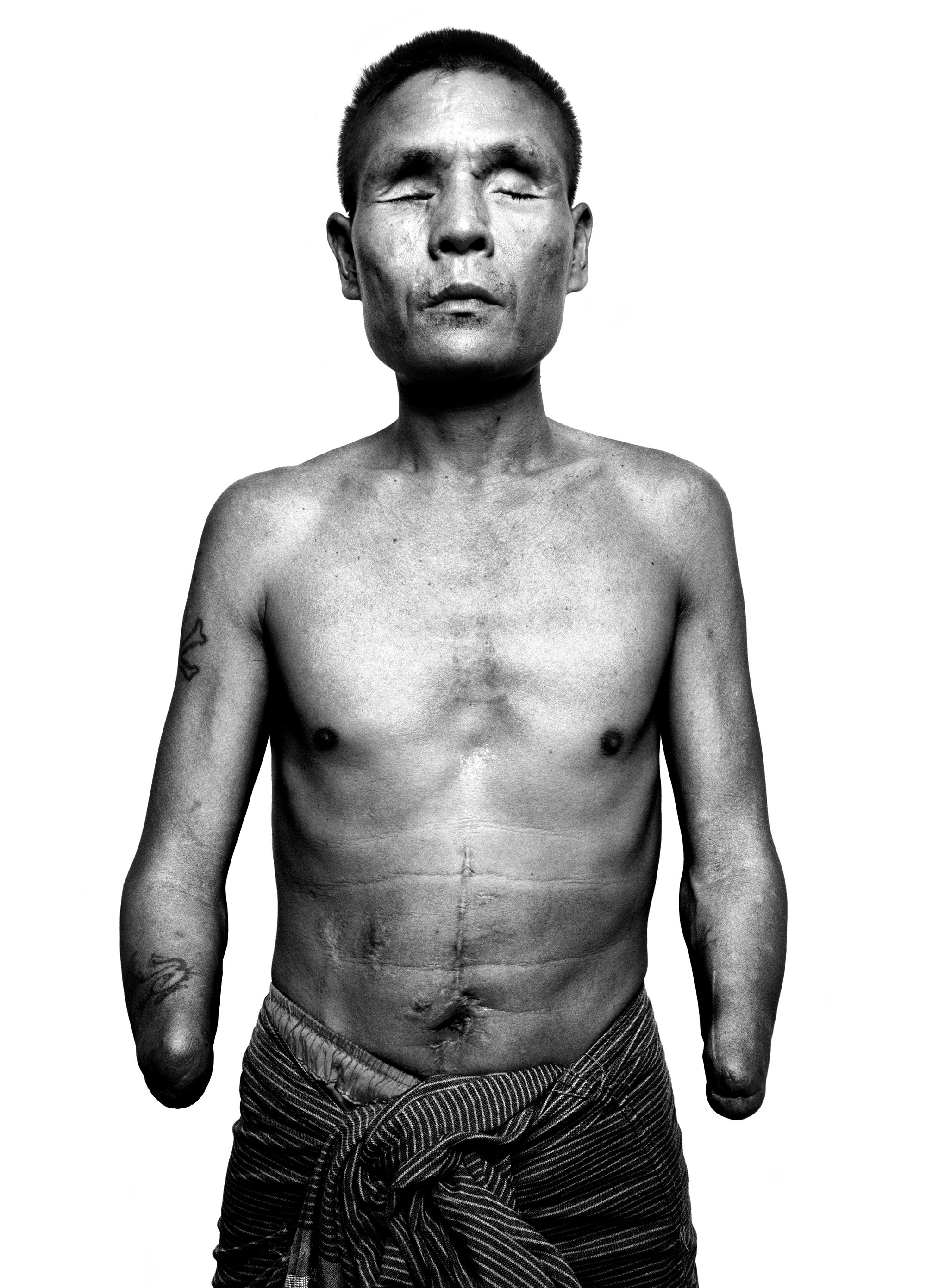

Gabriel Cervantes, Col. Burt Thompson, John Mardo

Thomas Berlin: Some images remind me of Dorothea Lange and Sebastião Salgado. For decades, few photographers used the word “humanity” with genuine empathy. I love that your book does—it surprised me to learn you’ve been on this path for twenty years.

Platon: The truth is, magazines weren’t interested in those stories. Maybe that’s why I was driven—because this work existed, these people had spoken, but no one was listening. The media filter kept blocking it. So I bypassed the system: make a beautiful book, and with a book comes press about the book—a different doorway. Everyone told me human rights don’t sell, that it’s a downer. Yet the book sold out online in ten days. I did countless interviews. People are interested—especially young people—when you present human-rights defenders not as victims, but as heroes.

Thomas Berlin: From what I've seen, I can understand that. You show these people with dignity.

Platon: And courage. Despite everything they’ve endured, they still stand up and speak. I know many powerful, rich, successful people who don’t have the courage to say what’s in their heart—for fear of judgment or cancellation. But a human-rights defender? They’ve already been judged, jailed, tortured; some have lost friends or family. And still, they speak. That makes you rethink what courage truly is.

Thomas Berlin: Your project shows that even strong media institutions can’t always be trusted to bring these stories to light. It’s good you built your own foundation. It makes me think of the German activist Rupert Neudeck from Cap Anamur — he helped boat refugees after the Vietnam War. He once said something like, “If you want to do good, don’t wait for the person in charge.”

Platon: That’s such a powerful thought. I’ve met many activists over the years, and one thing they all share is loneliness. Dr. Denis Mukwege, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate from Congo, is in the book—he once said to me, “It’s so lonely. Why isn’t there an army of us?” Breaking through that isolation, just being heard, is an uphill battle.

Thomas Berlin: So they want to be seen …

Platon: They want to be seen and heard—not for their own benefit, but because they know things we all need to understand. Yet we’re distracted, scrolling on social media through nonsense while our loved ones sit right beside us. With AI, content will only become less authentic, more manufactured. So the question is: will we still trade real moments with loved ones for something not even real?

Thomas Berlin: That’s a sobering thought.

Platon: I’m still an optimist. I hope we put our phones down and reconnect, because humanity is beautiful and powerful. Anger can be a strong release, but you can’t sustain it—it drains you, it destroys you. Our best moments aren’t when we’re angry; they’re when we’re joyful, or when something moves us so deeply that we cry.

Par Taw, a former child soldier in Burma.

Thomas Berlin: To really enjoy life, you need other people—to enjoy it together.

Platon: Exactly—together. In the book I worked with Pussy Riot, and Nadia Tolokonnikova has become a dear friend. She’s incredibly brave. During her trial in Russia, she delivered a speech almost no one noticed at the time. While researching the book—even though I already knew her—I went back and studied it carefully: what the judge said, what she said. That speech ranks among the greatest of our generation.

Thomas Berlin: I would have expected frustration or anger—but it was the opposite.

Platon: Me too. For a member of Pussy Riot—a hardcore punk-rock feminist—to stand in a courtroom cage facing the Russian system, knowing she’s going to prison, and yet speak with such compassion to call on us to be philosophers together, to seek truth instead of judgment, to stop labeling and dividing people—that’s extraordinary.

When they were released after two years, society misread them. People saw them as notorious celebrities rather than activists. Trendy magazines wanted cool photo shoots. After a while they asked themselves: What are we doing? We went to jail for women’s rights, for LGBTQ rights—and now we’re posing for coolness? They weren’t seen as defenders anymore, just as infamous figures.

Thomas Berlin: I saw your images of them after prison. They didn’t look cool—they looked human and vulnerable.

Platon: Exactly. It was a moment of respect and kindness, and a reminder of the price they paid—and might pay again. I had to earn their trust. Nadia was distant when we first met; I didn’t realize what she was struggling with—the way the media had embraced her for the wrong reasons, when all she wanted was to tell a meaningful story. The media defaults to celebrity, to fame and controversy; empathy and dignity are not its default settings.

Thomas Berlin: So people care about empathy, even if the media often don’t.

Platon: The people of the world do care.

Thomas Berlin: Then the media are wrong.

Platon: The media are wrong.

Thomas Berlin: I don’t think they were against Nadia—they just didn’t think her story would sell.

Platon: That’s the problem. Media has its own currency—fame, success, notoriety, power. It’s volatile, seductive, dangerous. I’ve seen incredibly talented people embraced and then consumed by bad values. It destroys them. Power corrupts and distorts; when no one tells you that you’re wrong, how much inner strength do you have left to police yourself? I’ve asked that question of many of my sitters—and of myself. I’ve seen world leaders campaign for responsibility and then abuse it once they have it.

Ester Faraja, 17, and son Jusuha. She was pregnant after being raped by soldiers in the Congo.

Thomas Berlin: Without checks and balances—family, friends, people who tell you the truth—that’s exactly what happens. When you photograph someone like Gaddafi, and someone like Nadia on the other side, what happens to you? Do you judge—“I like Nadia, I don’t like Gaddafi”—or how do you approach people you fundamentally disagree with?

Platon: That’s a big question—especially about my work—because media often simplifies things and misses the point. I’ve trained myself not to judge, but to be curious. It’s not for me to judge—that’s for history, and for you, the viewer. The more judgmental I am, the less I can see, and the less I can capture.

Thomas Berlin: So judgment blocks empathy?

Platon: Exactly. If my job is to reveal character, I have to open my senses, not close them. Judgment is the worst thing—it shrinks your ability to discover what truly matters. And we live in an age of judgment; everyone judges everyone else, but rarely themselves. Just because I photograph someone doesn’t mean I celebrate or condemn them. People confuse art with promotion.

Thomas Berlin: Your portrait of Gaddafi seems to be a good example.

Platon: It shows a defiant man, standing firm against the Obama administration at the time. I’m not naive about who he was. My friend Tim Hetherington was killed by his forces in Libya—targeted because he covered the crisis Gaddafi created. I know exactly what he did. My role isn’t to excuse him—it’s to remind people that these difficult characters hold immense power.

Thomas Berlin: You’re trying to show what makes them tick.

Platon: Yes. My job is to reveal their character so we can understand them better. People like to paint dictators as two-dimensional cartoons—but they’re far more complex. Bad people sometimes do good things; good people sometimes do bad things. Dictators can show charm, inspire others, even display humor. It’s uncomfortable to admit—but if we reduce them, we underestimate them.

Thomas Berlin: Yes, but we tend to view people as either good or bad, with nothing in between.

Platon: And then we’re surprised when they succeed and shape the world in dark ways. That surprise is our weakness. Churchill, for example, kept pictures of his opponents on his desk. Generals often keep portraits of their adversaries as a reminder that the other side also believes they will win.

Thomas Berlin: Niccolò Machiavelli wrote something along the lines of: “Keep your friends close, but your enemies even closer.”

Platon: It’s a lesson in humility. We mustn’t underestimate others just because we believe our moral compass is higher. We’re up against powerful, strategic forces. Take Putin—he’s extremely strategic. The more we paint him as a simplistic macho villain, the more we underestimate how deeply he understands our culture—often better than we understand his.

Edward Snowden

Thomas Berlin: That’s a frightening thought.

Platon: And it applies beyond leaders. We also need to understand people robbed of power as human beings, not as numbers. Immigration, for instance—it’s everywhere now, governments are collapsing over it—and yet it’s rarely humanized. Who are these people? Why did they come? What are they experiencing? True curiosity always risks discovering inconvenient truths.

Thomas Berlin: The more you know, the more uncomfortable it becomes sometimes.

Platon: Exactly. If you only seek confirmation for what you already believe, you trap yourself in an echo chamber—comfortable, but blind.

Thomas Berlin: It’s the same error to caricature dictators as it is to ignore the tragedy of refugees. We have to know more.

Platon: Absolutely. We have to be curious about the world. We’re becoming increasingly divided; we see political opponents as evil, dehumanized—because it’s easier that way. There’s a long history of dehumanizing the “other.”

Hitler was the master of it. Once you dehumanize a group, it becomes easy to abuse them—they stop being mothers, daughters, children, grandparents. They turn into numbers. And once that happens, we stop feeling.

Thomas Berlin: The longer it continues, the more people can justify doing terrible things.

Platon: Exactly. And now everyone does a little of it. If you’re on the left, you dehumanize the right—and vice versa.

Thomas Berlin: You, on the other hand, humanize. You give your subjects—defenders, victims and even dictators—a face and a voice. I’m curious about the balance between moral responsibility and aesthetic form. I saw war photographs at Paris Photo once—framed like luxury décor. It felt uncomfortable, seeing suffering turned into design. I know that's not your approach, but what do you think about it?

Platon: When I photograph someone, I’m never at a distance. I invite them to sit on the same little apple box that world leaders sit on—the exact same chair. It’s an invitation to collaborate. When you look at one of my portraits, you’re seeing a person who has chosen to share their story and their humanity with me. It’s a 50/50 dialogue.

Thomas Berlin: So for you, it's not just about taking a photo, but about sharing a view?

Platon: Exactly. In my human-rights work, the sitter wants me to share their story. We use my platform to amplify their voice. I promise to capture them respectfully and deliver their story within a context that honors their trust. That’s why I made the book—to control the narrative on behalf of my subjects and to show them as leaders of our time, with their blessing.

Thomas Berlin: So context is important—whether it’s a book, an exhibition, or a conversation.

Platon: Exactly. In exhibitions, I want to create cultural provocation. People walk through images of celebrity and power—and suddenly they come face to face with a little girl robbed of power, separated from her family. It’s jarring, and it should be. I’m not making aesthetic trophies for yachts.

Alu Banarji, civilian role player in a military exercise senario.

Thomas Berlin: That sounds that you’re leveling the playing field between the people?

Platon: Yes. If you see the same dignity in a portrait of a refugee that you see in one of Colin Powell or Condoleezza Rice, that’s intentional. I try to democratize power—to approach everyone with the same respect and curiosity. If my pictures were stripped of context and hung in a purely glamorous setting, I would have failed my friends. That’s why I fight to control the narrative—and why conversations like this matter. Through your platform, I can keep that promise. You become another vessel.

Thomas Berlin: I remember your line: “People are at their best when they can be natural. That’s the hardest thing to achieve as a photographer.“ How do you create a situation where naturalness can emerge—especially with the powerful, who are used to control, or with activists, who may lack confidence?

Platon: Many powerful people tell me the experience weighs heavily on them. One incredibly famous musician once said he hadn’t slept for three weeks because he was nervous about sitting on that box. People know the experience will be real—and they want to rise to it. My job is to earn their trust on set, whether it’s a president or an unknown person.

Thomas Berlin: That must take a lot of sensitivity.

Platon: It does. Each side comes with concerns—on one end, image and messaging; on the other, safety and exposure. People risk a lot to sit for me. I can never abuse that trust. I don’t have a government or corporation behind me, and I don’t want power. If I have anything, it’s cultural curiosity. With luck, we reach both head and heart.

Thomas Berlin: Do you have a metaphor for how you “tune in” to people?

Platon: It’s like tuning an old radio. Some days the signal is crystal clear; other days it’s static, and the slightest touch can lose it. People are like that—each one has a frequency. My job is to find it through questions, humanity, observation, respect. And each day, the signal might be slightly different.

Thomas Berlin: So you have to read the person first before you photograph them. But how?

Platon: You have to go into their soul. Someone once called it sorcery—a kind of mystical process. When you tune in—boom—you’re inside. It can be volatile, beautiful, inspiring, or dark. But if I enter respectfully, judgment falls away. Their legacy is what people will judge—not my session with them.

Muammar Gaddafi

Thomas Berlin: Maybe that’s why you can work with politicians across the spectrum—you don’t judge them.

Platon: It’s not my job to judge. My job is to connect, to capture an authentic moment, and then to hold up that image and provoke a discussion about the person’s legacy. Whether it’s an unknown defender or someone like Donald Trump, Putin, or Netanyahu—the process is the same.

Thomas Berlin: And those images have lives of their own.

Platon: They do. I’ve seen my portraits used all over the world—sometimes with horns Photoshopped on, sometimes as wanted posters. Pussy Riot once burned my Putin portrait in a protest. Netanyahu—people used my TIME cover of him as a wanted poster. Berlusconi—someone painted “FAIL” across it. Aung San Suu Kyi—the same thing. The same photograph works for both sides.

Thomas Berlin: So both supporters and opponents can use it—that proves you’re not judging. You deliver the mirror.

Platon: Exactly. Putin reportedly likes the portrait—it shows him strong, uncompromising, nationalist. His supporters like it too. And so are his opponents. It works for both sides because I caught a moment of truth.

Thomas Berlin: The “moment of truth” is a beautiful phrase—and hard to achieve. When do you sense someone is performing rather than revealing?

Platon: With George W. Bush, I felt performance. He had just left office—his first time facing his own legacy. Former presidents go through a painful period of reflection. The world was in crisis—the Iraq War, the 2008 financial meltdown—and Obama had just been elected. Many people were relieved Bush was gone. As a human being, he was confronting all that. Then he sits on my apple box—does he want to be captured forever in vulnerability, or as the easygoing guy he wishes to project? He put on a mask.

Donald Trump

Thomas Berlin: And you could feel that tension.

Platon: Absolutely. I struggled to shake it. But I’ve learned the mask can be just as revealing as what’s behind it. Sometimes the mask tells the real story. If someone wears one and we both see it, the question becomes why.

Thomas Berlin: This is especially the case when a mask becomes part of the composition, like an instrument in an orchestra.

Platon: Exactly. The good, the bad, the conflict, the harmony—it’s all part of the music if you’re willing to listen.

Thomas Berlin: Whether it’s Bush or a human-rights defender, your sitters often appear against a white background. What does that mean for interpretation? And what about black-and-white versus color—is that your choice or a client’s?

Platon: I’ve never seen magazines as clients—more as creative partners. They might tell me what they want, but that doesn’t mean they get it. My real “client” is the authentic experience.

If I felt something chilling, I might use the blue vignette behind Putin—it helped express the aura I felt around him. It’s a form of visual grammar—like why Shakespeare uses a comma for rhythm, or why the Beatles drop a minor chord to shift emotion. It’s intuitive, not scripted.

Thomas Berlin: So you start neutral and let the subject fill the space?

Platon: Exactly. I go in with a white background—nothing there—and let the person fill it. A great percussionist once told me that rhythm is the silence between notes; the stars are beautiful because of the black space between them. The white background removes distractions so you can see the essence of humanity—the twitch of an eye, a tilt of the head.

Thomas Berlin: And when do you decide to go with black and white?

Platon: It’s about mood. Color or monochrome—it’s grammar again. Each decision shapes the emotion I felt in that moment.

Thomas Berlin: You’ve developed a distinct visual language—white backgrounds, no distractions, deep blacks, luminous whites, and breathing midtones. The midtones with their details impress me because the harsh contrasts around them.

Platon: Details matter. Mies van der Rohe said, “God is in the details.” I was raised a modernist. My father was an architect; my heroes were Bauhaus. Simplicity, truth of materials—only what’s necessary. No decoration. Celebrate the material: concrete as concrete, wood as wood.

Elsheba Khan at the grave of her Son, US Specialist Kareem Rashad Sultan Khan

Thomas Berlin: And for you, the “material” is people?

Platon: Exactly. I took that philosophy and applied it to humanity. If someone’s angry, you’ll feel it; if they’re vulnerable, you’ll feel it. Be true to the material—be true to your subject.

Thomas Berlin: Hearing you, I can almost read your images through a Bauhaus lens.

Platon: That’s right (laughs). Good ideas are like water—they take the shape of the vessel. Truth, honesty, authenticity, curiosity, storytelling—and above all, human connection. If it’s real, you feel it. And in an age of AI, where we trade genuine experiences for artificial ones, real human moments will become the most valuable currency of the next generation.

Thomas Berlin: You once said, “If you want to photograph truth, look for humanity.” What have you learned about humanity from meeting people you didn’t know before?

Platon: That everyone is different—and every story is more complex than we imagine. Someone deeply vulnerable can show extraordinary strength. Someone very powerful can show extraordinary weakness. You should never go in with expectations. The most powerful man might be the most frightened; the most wounded little girl might be the most courageous. Our heroes can turn into villains, and our villains into heroes.

When I photographed the rapper P. Diddy, the image once symbolized swagger, confidence—“Bad Boy” energy. Now, it represents an absolute monster. Same with Harvey Weinstein—different industry, same story.

Thomas Berlin: So a photograph isn’t ever truly “finished.” Its meaning shifts over time.

Platon: Yes. As we learn more, we read the same image differently. Take my portrait of Weinstein—it still reads as truthful, but the truth you perceive changes. You now see arrogance, abuse of power, gangster mentality. It was always in the picture. Photography freezes time while life speeds up.

Thomas Berlin: Looking at your body of work, do you see yourself more as a photographer or as a chronicler of humanity?

Platon: I’m not sure I’m “a photographer.” I take pictures, but my real work is connection and storytelling. I’m a storyteller who happens to use a camera. I could have been a writer, but words didn’t come naturally—pictures did. The key is tuning into someone’s humanity and discovering what lies behind their face.

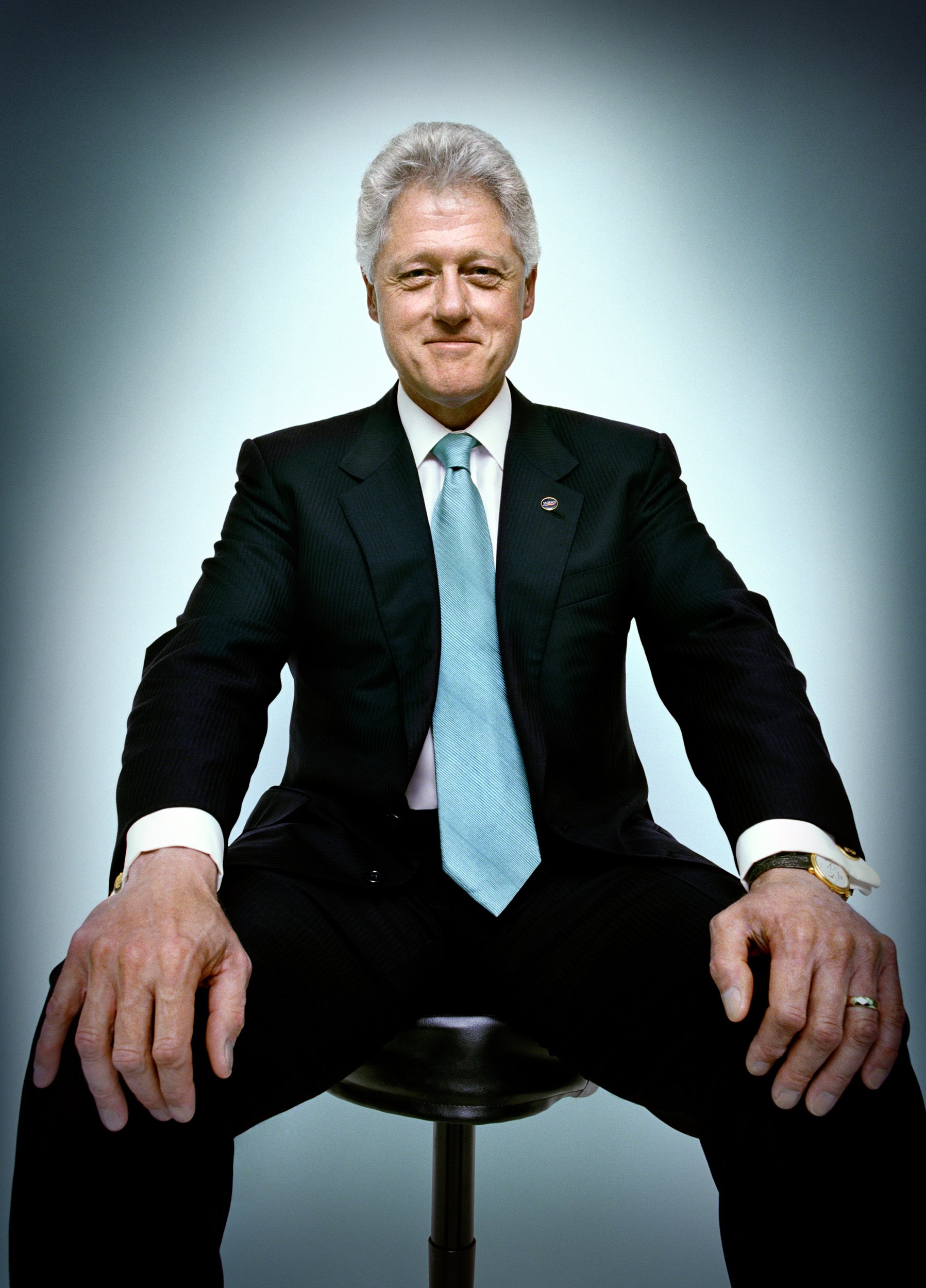

Bill Clinton

Thomas Berlin: Especially now, when authenticity feels fragile.

Platon: Exactly. With AI and all the noise, exchanging authenticity becomes vital. It’s scary to be honest—we all wear masks—but if we dare to be real, others see themselves in our struggles. That’s how we rebuild bridges.

Thomas Berlin: Is success possible if you think less about taking pictures and more about telling stories—the camera as just a tool?

Platon: The message is what matters. Find any way to communicate it. Musicians, writers, architects—we’re all in the same game: sending a message, holding up a mirror. The best artists aren’t trying to be ahead of their time; they simply see what’s already happening before society does. That often makes people angry—but without artists, we wouldn’t move forward.

Thomas Berlin: Like Van Gogh …

Platon: He sold nothing in his lifetime—by business standards, a failure; by artistic truth, one of the greatest who ever lived. He poured emotion, fragility, strength into his work—so true that people couldn’t relate at the time. But look now—young people stand in front of his paintings and cry. That’s what it’s all about.

Thomas Berlin: Young people often have their ownn approach to art. My little daughter once thought that the paintings in the museum had been painted by other children. This made art feel close and alive to her.

Platon: That’s beautiful. Children connect with art naturally and sincerely. Put the smartest, most powerful adult in a room with a child, and the conversation changes instantly.

When I talk to very smart people, I often ask childlike questions: “What does it mean to be successful? Explain it like I’m a kid.” It brings them back down to earth. Kids call you out when you’re not authentic. Sadly, as we age, we’re taught to pretend. We stop drawing. We all have to learn math at school—why not music and art at the same level?

Thomas Berlin: Couldn’t agree more.

Stephen Hawking

Platon: The higher up you go, the more pretending there is. My job is to call that out and say: let’s be real. You always know when something’s authentic—you feel it in your gut. My pictures push back against over-intellectualization. If they succeed, it’s because you feel something—evil, hope, joy, vulnerability—maybe even yourself.

Some critics say I glorify dictators or exploit the vulnerable. I don’t think they’re really looking. They’re not feeling what other people feel; they’re outside the club of humanity.

Thomas Berlin: Isn’t art, in the end, about feeling? Can art still create spaces for dialogue beyond left and right?

Platon: Absolutely. We must celebrate and support culture—because cultural leaders are the bridge-builders. During the Vietnam War, photographers helped change the narrative. Without artists, we wouldn’t even know what’s happening. It’s astonishing that America doesn’t have a cabinet-level Secretary for Culture.

Thomas Berlin: Really?

Platon: Yes, how can you be the most powerful country in the world and not have a minister for culture?

Thomas Berlin: Perhaps art is seen as unimportant or even risky. In Florida, a teacher showed Michelangelo's David and lost her job. In Paris, children sketch Rodin's nudes in the museum without anyone taking offense. It's about how society views art.

Platon: I think so. Artists tell us what’s happening. If you disregard artists, you disregard reality—at your own risk. When people say they don’t want culture, what they really mean is they don’t want to know. Musicians, painters, filmmakers—they’re tuned to the rhythm of life and hold up a mirror. We need that. We must be humble before it.

Thomas Berlin: How can artists reach people broadly without just reinforcing echo chambers?

Platon: Not every artist is good. You need both talent and commitment. Talent alone isn’t enough—you must dedicate yourself to refining it. Any society or corporation that doesn’t value culture damns itself. If you close your eyes and ears, you steer the ship blindly—and history always ends badly for such leaders.

Thomas Berlin: Let's talk about freedom – in your projects, you often ask the people you photograph: “What does freedom mean to you?” It's a simple but existential and very personal question. What does freedom mean to you – as a person and as a photographer?

Platon: Freedom is a big word—it can serve great or terrible things, depending on who wields it. A powerful person may define freedom as doing whatever they want without restraint. Champions of AI might call their race for dominance “freedom”. For others, it’s simply the right to speak their mind and live with dignity.

For me, freedom means freedom of ideas—listening twice as much as I speak. Two ears, one mouth. Two eyes, one mouth. Stay open, unchained by judgment. I’m curious—and curiosity itself must remain free.

Muhammad Ali

Thomas Berlin: You once mentioned a Russian mentor figure in journalism.

Platon: An elderly Russian woman in the book trained young journalists in free speech. I asked her what frightened her most after surviving the Soviet era, then a brief openness, and now a new form of control.

She said the first danger is journalists bending under government pressure and becoming propagandists. But worse, she said, is when journalists become social activists—when they stop being free and start telling the story they hope will happen instead of the one they witness. They want to shape history rather than describe it.

Thomas Berlin: That’s similar to photographers imposing their own values on an image instead of remaining neutral and letting others interpret.

Platon: Exactly. Judgment versus curiosity. Freedom lies in moving toward curiosity and away from judgment. Judgment is chains. Even ideas you find revolting must be understood—how can you change your opponent if you don’t understand and respect their strategy?

A dear friend of mine, journalist Lally Weymouth—daughter of former Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham—spent her life inviting people from different camps to dinner to talk with them. She asked everyone—from waiters to heads of state—“What do you think?” That is also freedom. It keeps life interesting.

Thomas Berlin: Let me ask something more personal. When you’re not photographing or involved in activism, what gives you energy—what grounds you?

Platon: I don’t socialize with movie stars or the people I photograph. I love being with my friends and family. I’m very quiet behind the scenes. My favorite time is walking with my wife, our dog, and our two teenagers.

These days, I’m even working with my kids—my daughter studies graphic design, my son is a filmmaker who helps me on projects. My greatest joy is having them in my orbit, watching them grow through culture, becoming talented and kind people.

Family time is precious. Visiting my 87-year-old mum in London, watching TV together, having dinner—that’s the best. I don’t need lavish parties. The magic is being with people you love, sharing time. That’s what heals me.

Thomas Berlin: Maybe that’s the most important time of all. In psychology, there’s an approach that invites you to view life from the end — to imagine yourself looking back on everything you’ve done, and everything you’ve lost. From that distant vantage point, the noise of daily worries fades, and what truly matters begins to surface.

Platon: The most important thing, yes. On my deathbed, I won’t wish I’d photographed two more world leaders. I’ll wish for one more day with my mum, my kids, my wife—at home, in slippers, peaceful. That’s privilege. That’s magic.

I’ve seen cycles—in life, in power. People rise to the top, then lose it all in scandal. I’ve watched it happen again and again. I know the pattern; I place myself within it and hope not to fall—but you never know. In the end, we lose it all. Sinatra said we’re just renting. We take nothing with us. We rent life, too.

Thomas Berlin: Thank you, Platon. This was one of the most moving conversations I’ve ever had. I think your words will stay with me for a long time. Is there anything you’d like to add in closing—something that feels important right now?

Platon: Treat people with respect and always stay curious. That’s it. If you can do that, you’ll be fine. It’s the long term that counts, not the short term. Keep looking in the mirror and ask yourself: Am I on the right track? You can’t judge anyone until you’ve judged yourself—and once you truly do, you realize you’re not perfect. Then you can’t judge anyone else either.

Platon welcomes visitors hon his homepage or on Instagram.

You should also see his project The peoples portfolio.

Your thoughts and reflections on this interview are very welcome here.

George H. Bush